Gabriel

When a wild animal comes into our care, it is not just physical needs we must address. The orphan’s nascent wildness must be nurtured, or it will be forever lost—and the young animal lose its ability to survive in the wild. The adult’s wild spirit must be protected and maintained in order for it to have confidence it can ‘escape’—and so allow us the time to help it heal for release.

It was early spring 2015 when we first encountered the eagle at the landfill. Often seen as the quintessential predator, eagles are in fact opportunistic and not above taking advantage of what we humans cause to be available.

It was cold and windy as we clambered over stones and clumps of debris to where the young eagle had been sighted at the edge of a field, and we first glimpsed the young bird—last year’s baby—moving clumsily along the tree line, rendered flightless and stumbling as the damaged wing dragged and caught under the talons of one foot.

A wild bird, a wild animal, will do whatever it can to elude capture, regardless of how badly it is injured. The wild ones’ imperative is to remain free. It is that Wild Spirit—that wild imperative—that is intrinsic to their survival.

When we were near enough for a final approach—we ran to surround him, and he suffered the indignity of capture.

Each wild species has its particular intelligence and, depending on its place in the food chain, individuals have an innate understanding of themselves relative to their environment. A healthy eagle has no natural predator and knows no boundaries. Its sense of omnipotence is justified—and so an injured eagle is peculiarly, exceptionally, and tragically lost. Grounded and vulnerable, it is prey.

When we handle an injured bird, especially for the first time, we must not approach like a predator. A firm but gentle restraint, a stillness of demeanor, a quiet voice—an aspect of respect is what is necessary to calm the wild one’s racing heart and keep its temperature from spiking dangerously. The wild one’s instinct will still tell it to run or fly away—but if we handle our first encounter just right, we start to build the trust that will be necessary for the wild one to heal.

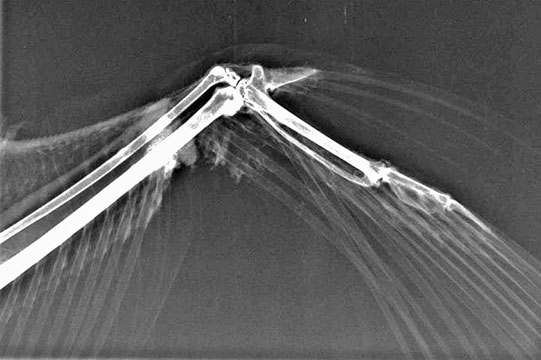

For this eagle, it was immediately obvious that healing was never to be. The skin and feathers had been pulled away for the length of the distal wing—fingers and forearm; the bones were broken and dead beneath. This eagle would live in captivity, or he would not live at all.

Because the bird was young and otherwise healthy, our orthopedic veterinarian, Dr. Scot Hodkiewicz, performed surgery to salvage what was left of the wing. Several months later we placed the eagle with an educator. He had lived through his first year, and his soft brown eyes and feathers were starting to show the signs of change.

The best wildlife educators understand that wild creatures are individual; they also recognize when a placement isn’t ‘right’ for a particular animal and, after a two-year absence, the eagle returned to us in spring of 2018. Now in his third year of life, the eagle’s head and tail feathers were dirty white and the light brown eyes glinted with gold. We carried his transport carrier up to the enclosure he had used as a young bird, opened the door, and waited.

In the first of the choices ‘Gabriel’ would make in his life with us, he chose to reenter his old home—no longer a ‘patient,’ but in a new and important role as ambassador and foster.

© 2025 Fellow Mortals, Inc.

W4632 Palmer Road | Lake Geneva, Wisconsin 53147

NOTE: All Visits are by Appointment Only —

Phone: (262) 248-5055 to make an Appointment