The Canada Goose and Fellow Mortals

It is not until the passing of time that we can see how one person, one incident, one wild creature can change everything forever. Fellow Mortals’ logo of the two swans, representing two lead-poisoned birds treated at our hospital—one struggling to lift into flight, one flying—represent our work and serve as a memorial and a tribute to the lead-poisoned geese who launched this organization into what it would become.

At the end of 1991, Fellow Mortals was a newly-incorporated organization and its founders, Steve Blane and Yvonne Wallace Blane, admitted about 200 animals a year. It was to be the last year of our wildlife rehabilitation “honeymoon.”

It started with a call from Rhonda Smith on January 17, 1992, who discovered the first of many lead-poisoned geese while walking her dog near the Riviera in Lake Geneva. It was not to end until many years later when, in October 1996, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency began a Superfund removal action of over 28,000 tons of contaminated soils and sediments from the site where that Canada goose and hundreds of others had been exposed to spent lead shot which they ingested while feeding—resulting in the worst case of lead-poisoning in Southeastern Wisconsin’s history.

74TH and friends

Both live and dead birds were retrieved in the rescue effort

After the National Wildlife Health Center in Madison, Wisconsin, confirmed that we were dealing with a toxin and not a contagious disease, Steve and I had a decision to make. The number of birds was staggering, and the financial commitment could end Fellow Mortals before it had really begun, but personally we felt we had no choice but to meet the challenge and trust that somehow we would handle it.

In the next few days after that first call, another 150 live geese were rescued from the dangerous ice of Lake Geneva and brought to Steve and Yvonne’s home for treatment. There was no facility, only our bedrooms, living room, kitchen and porch in the small home located in rural Delavan. And then there were the kennels set up hastily in the back yard, tarped against the bitter cold and bedded deep with straw with heat lamps providing pools of warmth, and the most critical birds brought into the kitchen and living room to nestle on rugs next to the baseboard heaters.

Then, as now, we reached out to our state and federal agencies for help. It is largely due to our Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources wildlife manager, Tom Becker, and Special Agent Lucinda Schroeder, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, that we succeeded. Their belief in our abilities and assistance with personnel, advice, caging and evidence collection and preservation made the effort a success. They contacted other wildlife rehabilitators to come and help with the rehabilitation effort and our local Audubon Society, Wisconsin Conservation Corps, area environmentalists and sportsmen all came together to help Steve with the rescues.

The weakest birds were brought into our home

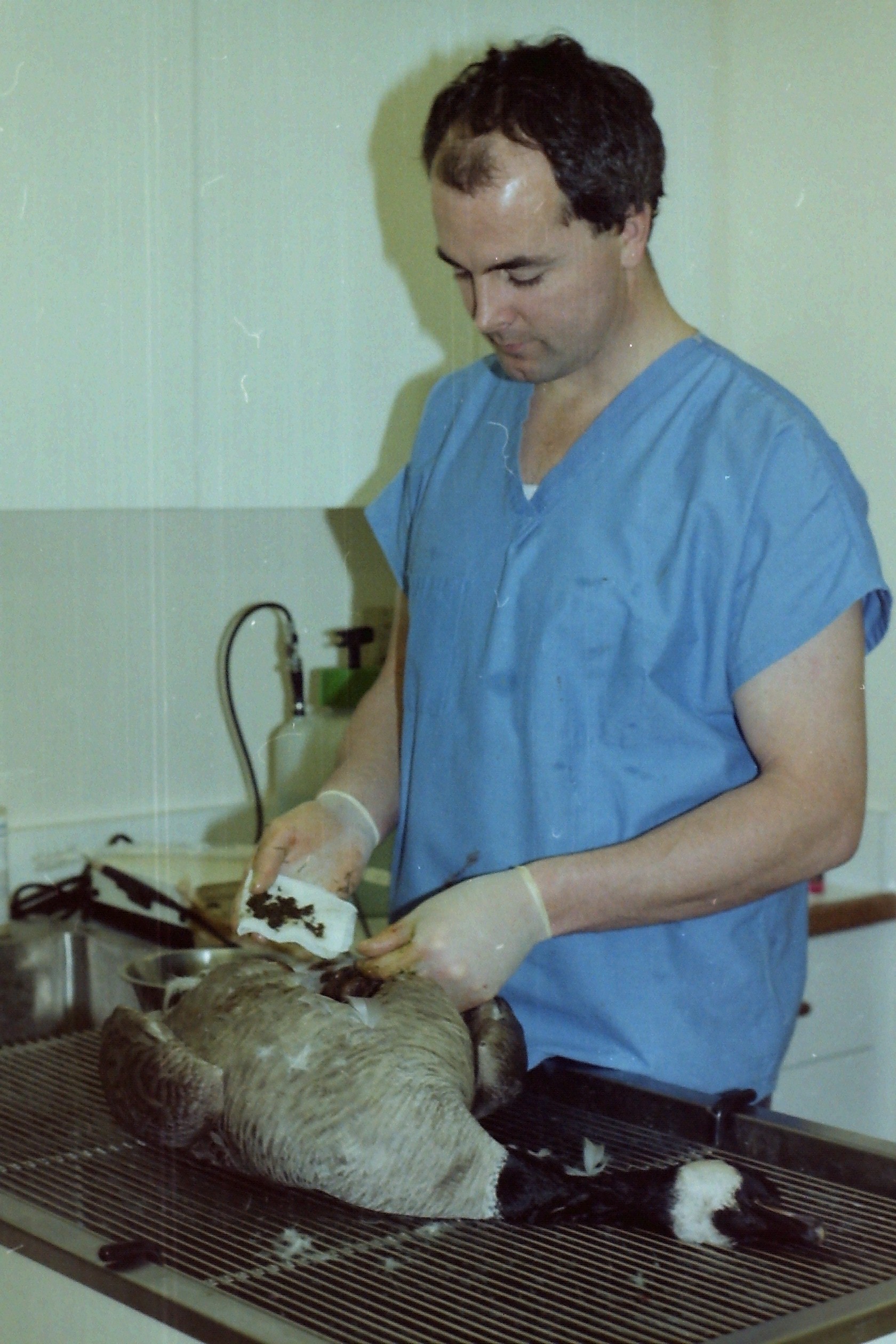

Actual rehabilitation of the geese could never have been handled by two people alone. Dr. Pat Hourigan, who had recently opened his clinic in Richmond, Illinois, performed the first procedures and then instructed the rehabilitators how to do them. Rick Cochran, a Racine County rehabilitator, was at Yvonne’s side for almost six weeks straight to administer injections of Calcium EdTA and help with lavaging lead pellets from the geese’s ventriculus (gizzard)—a long, stressful procedure for both goose and human. Rehabilitators Ted and Lisa Heberling, Terri Cochran and Kathy Sawicki were on hand when they weren’t at work. Blood tests and radiographs alternated with the lavage treatments until they blended into what seemed like normalcy.

Dr. Pat Hourigan with lead-poisoned goose

Lavaging process took two teams

Outdoor cages housed dozens of lead-poisoned geese

Injections were given three times a day at the outset

I am still heartsick when I remember the first task every morning that winter—going out to the holding areas to collect the dead bodies and bring the dying into the house for warmth. It was 74TH, the bird pictured in the kennel above, who was our totem during this terrible time. He represented all of the birds who were rescued, fought to survive and lived or died. Releasing him on Easter Sunday lifted the burden of those heartbreaking months.

When rehabilitators are criticized for losing sight of the forest for the trees because we choose to deal with need on an individual basis—take note: the bulk of research done involving wildlife medicine is funded, and the texts written by, people involved in experiences such as this. In a crisis of this magnitude, even individuals of an endangered or threatened species would be lost without the volunteer efforts of wildlife rehabilitators.

The video tapes we made were later used for training Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources wildlife biologists in identifying lead poisoning in waterfowl; the lavage procedure designed by Dr. Pat Hourigan was written up and presented in papers to the National Wildlife Rehabilitators Association and the International Wildlife Rehabilitation Council. The procedure taken for granted today was new in 1992.

The cost of the lives saved cannot be told in dollar amounts alone, for they were also paid for by the many people with disparate interests who invested their time and emotion in a seemingly hopeless cause for one reason—belief in the value of individual life.

Photo by Ted Heberling

Geese with young at the release site later in 1992

In the 28 years since that winter, Fellow Mortals moved to its new location outside of Lake Geneva. Nearly 50,000 animals have received care from our hands. We have built a state-of-the-art hospital, heated indoor habitats, large flights—all for the sake of the injured and orphaned wild ones who, like those geese, saw their wild lives interrupted by tragedy caused as a result of human actions. The facilities are much better, but we rehabilitate no differently than we did then, for the promise is still the same, as is the value we will always place on individual life.

© 2025 Fellow Mortals, Inc.

W4632 Palmer Road | Lake Geneva, Wisconsin 53147

NOTE: All Visits are by Appointment Only —

Phone: (262) 248-5055 to make an Appointment